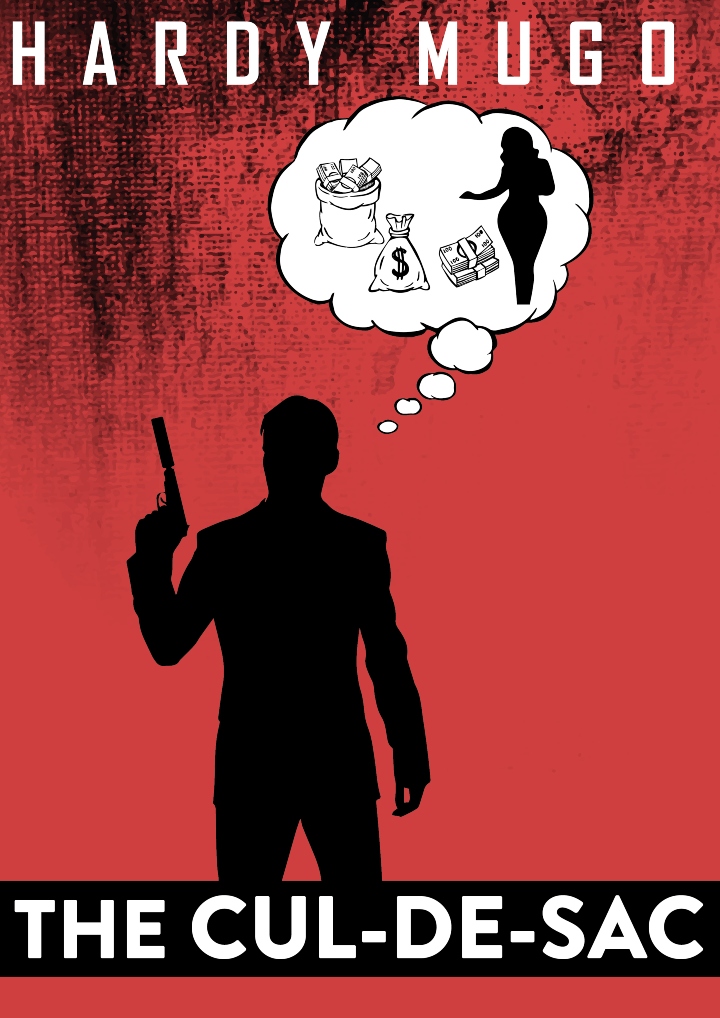

Synopsis

The cul-de-sac is a story of a young man who learns that he has cancer and believes his time is running out.

He moves from Mombasa to Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, in an effort to locate his college love, whom he considers to be the most important person in his life.

He eventually decides to join a gang to help him make ends meet and achieve his ultimate objective of marrying Shillah. The story that follows is exhilarating.

This short story is protected by copyright. Any unauthorized reproduction or distribution, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited and may result in legal action.

This includes posting the story online, whether in its original form or in a modified version.

If you wish to share this story with others, please do so by sharing the link to the original publication or by obtaining permission from the author.

Thank you for respecting the author’s intellectual property rights.

CHAPTER ONE

We headed straight to Bomu Clinic to see Dr. Tossa, the physician. At the facility, we were asked to make a booking as Dr. Tossa visited the hospital only on Tuesdays and Fridays.

It was on a Thursday, and that meant Friday was fully booked. We were therefore booked for Tuesday the following week, then headed home.

I started preparing supper while chatting the evening away with my dad.

Currently, he had noticed my deteriorating state of health and would seize every moment to assure me that all would be fine in due time.

Dad would assure me that the pain was not going to last. And during critical times in life, sometimes words of assurance have to characterize the person uttering them.

I had seen my father weave through numerous odds in life and come out of the situations stronger.

But his resilience and ability to stay sane despite the odds were simply amazing.

I can’t remember a time in my life when I heard my dad make a negative confession about his fate or any other situation.

His positive attitude was beyond reproach.

After a hearty supper, we prayed and retired to our beds.

But sleep eluded me that night as racing thoughts invaded, however hard I tried to keep them away.

What if the findings came out that I had a serious condition, like, say, cancer? What would I do? What of my parents?

If I died young, my parents would certainly be heartbroken.

I believe the greatest inspiration in a man’s life is the woman he loves.

First, that woman happens to be the boy’s mother. Later, the mother is replaced by a girlfriend or a wife.

I had numerous relationships with girls from high school to college, but there was something that never seemed to satisfy a part of my being.

Then, in my final year of university, Shillah appeared out of nowhere and seemed to fill an unexplainable void beyond love.

We became so attached that we even discussed the number of children we would have in the future.

Despite our seemingly strong attachment, marriage was unlikely as Shillah’s parents were quite wealthy, and on many occasions I doubted if they would entertain the thought of having their daughter married to a young man whose only strong point was a university degree.

A university degree? Nowadays, it almost counts for nothing in Kenya. After all, almost every youth seems to have one or is in the process of acquiring one.

But it was the gut feeling of the looming likelihood of not being able to spend my life with her that I found most upsetting.

Social-economic disparities aside, two incidents during the formative days of our night outings, a few weeks before we parted ways, have remained etched in my mind.

“By the way, I’m from a humble family,” I said.

“I know. “I recall you telling me there are four boys in your family and the size of your mugunda (farming land) is less than two acres,” Shillah had replied.

That was the first incident.

The second incident is the day she told me we were not meant to be together.

I tried to show her otherwise, but I failed flatly. And what’s more, I’m quite poor when it comes to persuading girls when they show the slightest sign of nagging.

But Shillah’s case was different; I put in a considerable effort trying to convince her that we were meant to be together.

To be honest, I initially thought it would be impossible to continue living without her, but as days passed, our memories together became hazy, and we drifted apart.

But we would say “hi” whenever we met along campus corridors. Again, I later thought our parting was good riddance given that I was a final-year student and Shillah was a freshman.

I reasoned that it was better that she had shown her true colors early enough instead of having another guy play “assistant Jacob Mwangi” after I graduated and left her in college. Sleep wrestled with me, and I yielded.

*************************************************************************************************************

On Tuesday, I went to see Dr. Tossa. There were nine other patients ahead of me in the queue.

The ten of us were enough for Dr. Tossa’s day. He spent between 30 and 45 minutes with each patient.

During his time with a patient, he would listen keenly as he scribbled notes on the patient’s card.

My turn came, and I entered the room and took the patient’s seat.

“How are you doing, Jacob?” He said this while looking at the name on my card.

“Fine,” I answered.

“That’s good. Now tell me what’s ailing you.”

I described every symptom I could remember. He listened keenly, correcting me only when necessary, like when I referred to leg tremors as palpitations.

“Those are called tremors,” he corrected.

“Ok, lie on that examination bed,” Dr. Tossa commanded after I had described my symptoms.

According to his physical examination, which included, among other things, tapping the sides of my stomach, he told me that there was no cause for alarm.

That statement sounded so trite and boring. Before, I had seen a number of doctors who had diagnosed me with malaria, typhoid, or brucellosis.

The annoying thing is that doctors kept looking out for the same diseases wherever I sought treatment.

I was waiting to be told the same thing by the physician.

“You told me you experience pain in your middle back?”

“Correct,” I replied.

“Now then, I don’t take chances with my patients. I want thorough tests to be conducted so we can establish exactly what is causing you sleepless nights,” said the doctor.

The following day was a busy day for me as I went for comprehensive tests. I began with a complete haemogram of blood and CT scans.

I took the blood tests, chest X-ray, and CT scan and headed to an imaging center in Mombasa town.

I paid and waited in line for my chance.

I took the two barium tests, which indicated I had duodenitis. Ultimately, the tests showed there was a small tumour on the head of my pancreas.

At home, I showed my dad the imaging report.

This time around, dad, who is the epitome of calm, was alarmed by the turn of events.

He spread the loose fabric cover on the armrest of the sofa he was sitting on.

The latter gesture from dad meant he was either angry, uneasy, or disturbed.

On this particular day, the news of my present situation had shaken my old man to the core of his being.

However, I guess the peace and calmness on my face served to bolster the sparkle of calmness in his being.

Dad said that given that we weren’t medical experts, it would be wise to let the doctor give me the way forward instead of wallowing in speculations.

Yet a voice within kept reassuring me that I was going to conquer whatever illness it was.

In my mother tongue, there is a saying that a child with a guardian does not play with feaces, meaning a child with a mentor has better chances of succeeding against life’s odds.

Dad had been such a great inspiration in my life.

I prepared supper, which we ate quietly while watching the day’s news.

This very day, a Member of Parliament had, during the proceedings in the house, referred to a senior minister as his shoga.

In Kenya, the word “shoga” was a disdainful reference to homosexuals, while in neighboring Tanzania, it meant a friend, and the term was mostly used between women.

When pressed by the Speaker of the House to elaborate on the reference, the outspoken MP stated that he had used the term in the Tanzanian context.

Knowing the two were friends and business partners, the entire house burst out laughing.

“That’s what will happen to you when you marry Shillah,” my dad joked.

“They say kuringa thimo when we say kuhura thimo,” he added. We both laughed at Shillah’s people’s dialect.

The first phrase spoken in my region would imply that the person was not making a phone call but literally smashing the phone into pieces.

But what baffled me that night was my dad’s belief that at one point in time Shillah would become my wife.

I failed to understand my dad’s insistence, despite having previously stated that I had no intention of marrying Shillah. He still kept insisting that the two of us were meant to be together.

But I suspected it was my mum who kept adding embers to the romance story between Shillah and me.

And here’s why:

Immediately after clearing university, I traveled up country to assist my mum on the farm, and I guess that’s when I told her about my love for Shillah.

I guess I told her a lot about this angelic girl, and she liked her from my detailed description even though they had never met.

I vividly remember that on one night when I came down with tremors and stiff joints, my mother came and kneeled beside me and prayed.

But what moved me to tears was her solemn prayer that God spare my life so that she could see my children with Shillah.

************************************************************************************************************

Friday afternoon found me at Dr. Tossa’s office. I waited impatiently as the patients entered the doctor’s room, only to leave about an hour later.

Luckily, my phone was internet-enabled, and I browsed tens of websites as I waited for my turn. I wanted to know everything I could possibly muster about cancer.

This is how my turn came, almost as a surprise.

“Number 10!” the nurse called.

I awoke as if from a deep sleep and made my way to the doctor’s office.

After exchanging pleasantries, I handed the complete blood test to him, along with x-rays. One chest x-ray and two barium meals were examined.

After scrutinizing the two, I saw the doctor’s face crease for a moment.

He sighed and then looked at me with pitiful eyes.

Dr. Tossa told me that all along he had suspected the presence of a tumour on my pancreas.

“But I want you to go for further tests at Texas City Hospital,” he said. Despite it being expensive, this was a well-established hospital whose services were known to be of high quality.

I could feel my mind racing, but I smiled to ward off the uneasiness that was written all over my face.

“Now, Daktari, how much time do I have on this earth?”

“You shouldn’t worry yourself to death, Jacob.” “And importantly, it is good to remember that God has the last word in everything,” said Dr. Tossa.

But it was pointless. In the recent past, I had read voraciously about cancer and metastases. I had also read that pancreatic cancer was one of the cancers with poor prognosis.

So much so that as we continued our discussion with Dr. Tossa, the good doctor dropped his guard and started discussing the issue with me as he might have done with a fellow medic.

“It looks likely the pancreatic tumour is a secondary tumour. Most probably, the primary tumour is in your liver. Your thyroid and adrenal glands are also affected. “That explains your low energy,” noted the doctor.

I listened attentively, my calm demeanour encouraging the good doctor to disclose even more.

And at the time, I was feeling relieved.

The doctor further explained that the tumour on the head of the pancreas was the cause of my glucose intolerance. Most of the foods I ate seemed to have an effect on my body.

In fact, there were only a few foods I could eat without experiencing serious brain fog and fatigue.

That said, the physician prescribed some pain relievers to deal with the pain.

In the evening, I narrated to Dad the whole issue. As usual, he advised me not to worry as things would surely get better.

“I recommend that you travel to Nairobi to see the oncologist,” dad advised.

“I’m not seeking any further treatment,” I said.

“I’d be very disappointed in you, son. You know how much I want the best for you. And you need to be in good health to chase and realize your dreams,” he said.

I did not say a word. And that is how my dad understood that I had made up my mind.

And what’s more, my dad understood there was very little one could do to sway my opinion once I made a decision.

And that’s how he abandoned his bid to have me pursue treatment.

Early the following day, I received a call from my mother urging me to seek treatment in Nairobi.

Even though it was not easy to say no to her, I tactfully managed to plead for “more time” to consider my options.

“And please don’t disappoint your dad and me. You are well aware of the high expectations we have for you,” mum concluded.

What do I do? I thought. Do I agree to seek treatment or just start an herbal regimen?

An idea crossed my mind. I will search the internet for the best herbal remedies to help me get better.

I searched the World Wide Web, moving from one link to another until I thought I found what I was looking for.

I decided to try a concoction with cumin as one of the ingredients. I had another one that included pomegranate, but I dropped it as it was rather labour-intensive as far as the preparation was concerned.

After two days, I felt better and a bit relieved. The bloating and the dull, fiery ache that radiated to the back had eased.

The only thing that was now bugging me was the lightheadedness that seemed to persist in the morning hours.

This short story is protected by copyright. Any unauthorized reproduction or distribution, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited and may result in legal action.

This includes posting the story online, whether in its original form or in a modified version.

If you wish to share this story with others, please do so by sharing the link to the original publication or by obtaining permission from the author.

Thank you for respecting the author’s intellectual property rights.

THE CUL-DE-SAC: CHAPTER TWO